By Steve Sucato

A full house of enthusiastic dance fans welcomed the Martha Graham Dance Company back to Cleveland Saturday night for the first time in nearly two decades.

Presented by DANCECleveland and Playhouse Square, Graham 100, at KeyBank State Theatre, was part of the company’s worldwide 100th Anniversary Tour.

The company delighted the audience with a mixed repertory program of works spanning the company’s century of dance excellence.

It began with late choreographer Martha Graham’s most famous work, 1944’s “Appalachian Spring,” set to composer Aaron Copland’s iconic original score of the same name.

Often cited as Graham’s contribution to the WWII war effort, “Appalachian Spring” exemplifies American determination in its depiction of a young frontier couple on their wedding day.

Danced on a minimalist set designed by Isamu Noguchi that featured a house outline, a fence, a bench, and a Shaker rocking chair, the work glimpsed the joy of the frontier couple dreaming of the future and starting a family, tempered by a devotion to God.

Dancer Ann Souder as the bride and Lloyd Knight as the Husbandman beautifully embodied those roles, skillfully performing Graham’s illustrative choreography.

The couple was joined onstage by Ane Arrieta as a Pioneering Woman, a mother-like figure to the community, and Jai Perez, a stoic Preacher, and his four young female followers, spellbound by him as much as their faith, who trailed after him like ducklings in a row.

Costumed in prairie dresses and bonnets, the followers performed the bulk of Graham’s most whimsical and engaging choreography in the work, moving in square-dance patterns and executing paddle turns, curtsies, skips, and duck-walking with dress bottoms in hand.

The most dramatic choreography came in two solos later in the work. One, performed by Knight, who appeared concerned about being called to war or a post-war future, and the other by Perez, who danced with the fervor of a fire-and-brimstone sermon.

A shining example of Graham and Copland’s artistic genius, “Appalachian Spring” endures as one of dance’s most significant works, with a timeless message of hope and determination that remains relevant today.

Next, “We the People” (2024) by former resident choreographer of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Jamar Roberts, provided a 21st-century reminder of American determination in the face of an America that does not always live up to its promise.

Danced to an American folk music score by Pulitzer Prize-winning musician Rhiannon Giddens, “We the People” touched on themes of protest and coming together for a brighter future.

The work was delivered in multiple sections, each beginning in silence. The first saw dancer Leslie Andrea Williams emerging from a cloud of stage fog to reach center stage. There she shifted her body back and forth in place, pounding at her chest with a defiant frustration. She was then joined by the rest of the 11-member cast, performing movement that alternated between sharp and punctuated and slow and soft, echoing the tone of Giddens’ music.

An undercurrent of seething ran throughout the work and rose to the surface at times, reflected in marvelous, stylized choreography performed by the dancers, including evocative solos by Knight and dancer Laurel Daily Smith.

Roberts’ work expressing lament over a flawed America was followed by Graham’s “Lamentation” (1930). One of the choreographer’s earliest works, the short solo for a dancer costumed in a stretch-fabric tube and seated on a bench, is described as an embodiment of grief.

A modern dance classic, I have seen it performed multiple times by multiple dancers. Doing the honors Saturday night was Williams, who, while delivering a spot-on technical interpretation, lacked expressiveness equal to the weight of the solo’s emotion. Thus, the deft bending, writhing, and contorting of Williams’ body amounted to little more than just that.

After a respectable performance of another of Graham’s WWII-era works, “Steps in the Street” (1936), by guest dancers from Case Western Reserve University’s Dance Department, led by Megan Gregory, the program concluded with all-the-rage Israeli-born German choreographer, Hofesch Scheter’s “Cave” (2022).

A work celebrating the release felt after the recent pandemic, it expressed a different kind of joy from that of “Appalachian Spring,” and one the pious characters in it might have seen as reflective of Sodom and Gomorrah.

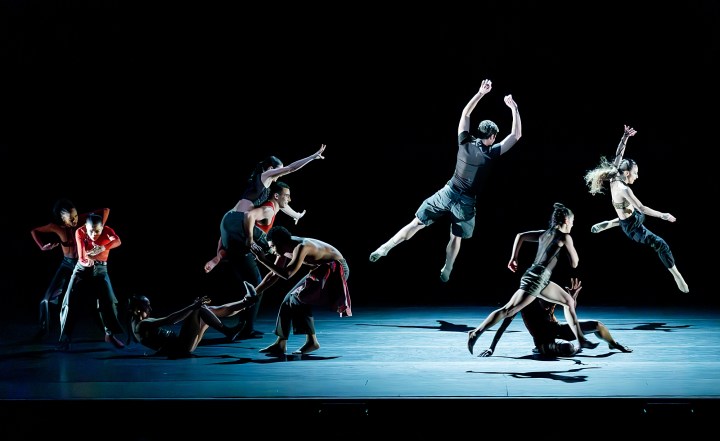

It began slowly with the muffled, distant sound of techno music one would hear in the parking lot of a club before entering it. The work’s cast of eleven engaged in slow-burning social dance movement as the music’s bass notes rumbled and shook the theater.

As the music built in intensity and ear-assaulting loudness and the dancing sped up, it was as if being dropped into the middle of a rave. And what a dance party it was. The dancers, en masse, grooved in unison, jumping and hopping, hands in the air, at times with their backs to the audience. The reverie was also sprinkled with bravura solo efforts, none finer than the company’s tallest dancer, Ethan Palma’s forays into the spotlight, where he spun with the pace of a figure skater and leapt like a gazelle.

Well-crafted and ebullient, “Cave” capped a memorable evening of dance that celebrated Graham’s legacy, while looking to its next 100 years.